ALS patients sometimes say that there is a "special skin" associated with ALS. It would appear that this is true. A new study shows that the TDP-43 pathology develops throughout the body, up to ten years before diagnosis.

Understanding the mechanisms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) remains a major challenge in neurodegenerative research. Although the diagnosis of ALS is based on motor symptoms, the underlying pathology develops silently for years. A growing body of evidence suggests that these early pathological events could be detectable outside the central nervous system (CNS), well before the onset of clinical symptoms.

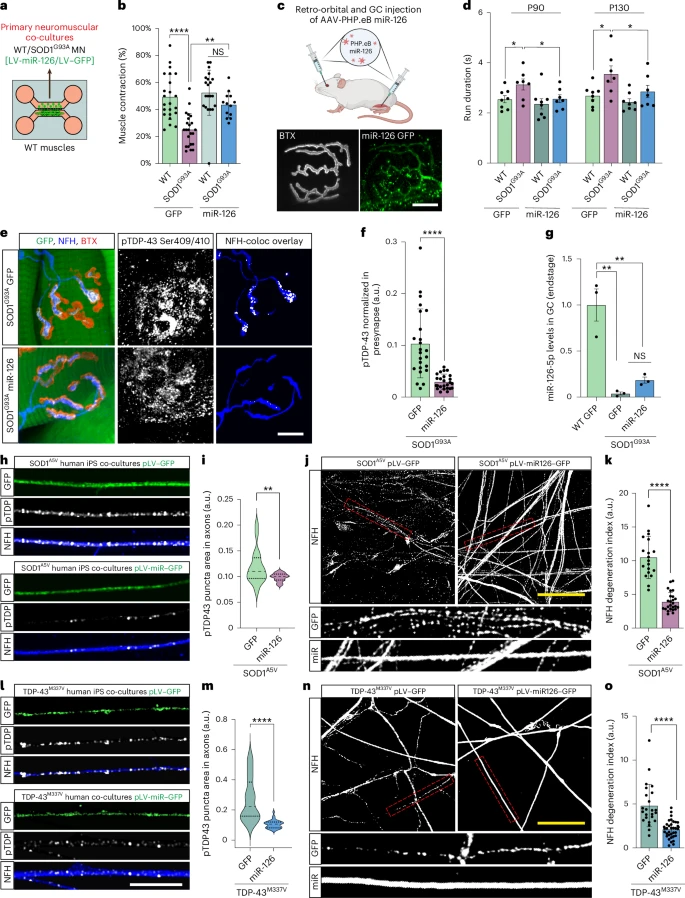

A recent study has explored this possibility in depth. The scientists used new tools to explore the TDP-43 pathology. Conventional staining with anti-phospho-TDP-43 antibodies did not reveal any aggregates in the muscle samples. This study highlights the potential of RNA-based detection tools for the early diagnosis of pathologies.

Using sensitive molecular tools, the authors examined the early manifestation of TDP-43 pathology in the peripheral organs of individuals who later developed ALS across several databases. Their findings highlight the skin as a particularly promising source of pre-symptomatic biomarkers, with the pathology sometimes detectable more than 20 years before the onset of symptoms.

The first part of the study examined tissue biopsies from eight different organ systems, taken from living individuals who later developed ALS. Importantly, the authors employed two novel, highly sensitive approaches. They initially detected abnormalities in the skin of 7 patients, and then in various non-brain sites in the bodies of 17 patients:

Skin

Muscle

Colon

Gallbladder

Lymph nodes

The affected cell types share a common developmental origin with the central nervous system.

In these individuals, abnormalities appeared:

Up to 11 years before the onset of symptoms in the skin

Up to 14 years before the onset of symptoms in the lymph nodes

1 to 2 years before the onset of symptoms in the gastrointestinal tissues

In one person who had two biopsies performed in the same location several months apart, early pathology appeared between the two biopsies. This suggests a real-time transition from normal to abnormal tissue, potentially reflecting a phenomenon of "phenoconversion."

In the validation cohort, a wide range of anatomical sites were affected: head and neck, trunk, perineal region, and limbs. The pathology was diffuse regardless of the sampling site. Muscle tissue also exhibited previously undetectable abnormalities. Sweat glands showed the most consistent and intense signal, making them excellent candidates for the development of quantifiable biomarkers. Areas protected from the sun had a higher pathological burden than sun-exposed areas.

These results also suggest widespread peripheral immune and vascular involvement.

These results underscore the potential for developing minimally invasive early detection tests using skin biopsies. Although further studies are needed, particularly with larger and more diverse cohorts, the data presented suggest that cutaneous TDP-43 tests could become valuable tools for early diagnosis, risk assessment, and future clinical trials aimed at pre-symptomatic intervention.

Implications for ALS Research and Treatment

1. Reassessment of Pathogenesis

These results support the hypothesis that ALS may be a TDP-43 proteinopathy predominantly affecting the central nervous system, rather than a disease exclusively affecting motor neurons. Researchers must now determine whether pathology of peripheral tissues (such as sweat glands in the skin or nerves in the intestine) is simply a transient phenomenon or actively contributes to disease progression. It is possible that peripheral pathology fuels CNS pathology in a phenomenon of "retrograde degeneration," overloading motor neurons in the spinal cord and brain.

2. Expanding Therapeutic Targets

While ALS is a systemic disease, drug development should not focus solely on the brain and spinal cord. Therapies targeting the underlying cause of TDP-43 protein dysfunction in peripheral tissues are becoming increasingly important.

More readily accessible sites, such as skin or blood, could be easier to administer while offering protection to motor neurons.

3. Early diagnosis is now possible

As the study has shown, the diffuse nature of the pathology makes it an ideal candidate for early diagnosis. A skin biopsy becomes a relatively non-invasive and accessible tool for detecting the disease decades before the onset of clinical symptoms, thus providing a crucial window for preventive therapies.

In short, the diffuse nature of the pathology does not call into question the involvement of motor neurons, but rather places it in context. It strongly suggests that motor neuron degeneration is the serious clinical consequence of a more widespread systemic cell failure, caused by a dysfunction of the TDP-43 protein.

When pathologists examine the spinal motor neurons of patients with SOD1-related ALS, the nuclei generally appear normal: the TDP-43 protein is always present, and abnormal aggregates are rarely observed. This is why SOD1-related ALS has been considered "TDP-43 negative."

When pathologists examine the spinal motor neurons of patients with SOD1-related ALS, the nuclei generally appear normal: the TDP-43 protein is always present, and abnormal aggregates are rarely observed. This is why SOD1-related ALS has been considered "TDP-43 negative." Analyses statistiques contestables

Analyses statistiques contestables

The authors found that key immune signaling proteins, specifically those containing Death Fold Domains (DFDs) (like ASC, FADD, BCL10, MAVS, TRADD), exist in a unique physical state inside our cells called metastable supersaturation. These full-length adaptors retain nucleation barriers and are able to exist supersaturated in cells. In contrast, many receptors and effectors do not. This localizes the “spring-loaded” behaviour to central adaptors that link receptor sensing to downstream cell-fate decisions.

The authors found that key immune signaling proteins, specifically those containing Death Fold Domains (DFDs) (like ASC, FADD, BCL10, MAVS, TRADD), exist in a unique physical state inside our cells called metastable supersaturation. These full-length adaptors retain nucleation barriers and are able to exist supersaturated in cells. In contrast, many receptors and effectors do not. This localizes the “spring-loaded” behaviour to central adaptors that link receptor sensing to downstream cell-fate decisions.