I am pleased that two new articles bear a similar message: That neurodegenerative diseases can't be understood with the paradigm acquired with communicable diseases.

This paradigm tells us that as the pathogen is quite homogeneous, so is the disease phenotype. This is indeed wrong for non-communicable diseases like cancers and is even wrong for some communicable diseases like COVID-19 where the pathogens have heavily mutated.

One of these articles is "Serena Verdi et al, Personalizing progressive changes to brain structure in Alzheimer's disease using normative modeling".

The authors looked at 3233 brain scans. The number of non-standard brain structures increased over time in people with Alzheimer's disease. Patterns of change in outliers varied markedly between individual patients with Alzheimer's disease.

The authors say: "I think we need to pivot towards a new way of thinking to get away from the idea that this (brain) area is important, this area isn't". The big picture and the individual variability contained within it, is what counts.". Some of this individual variability may stem from the fact that many people with Alzheimer's have more than one cause of cognitive illness.

This idea that "we need to pivot towards a new way of thinking to get away from the idea that this (brain) area is important, this area isn't" is certainly important when we think of other neurodegenerative diseases such as ALS or Parkinson's disease.

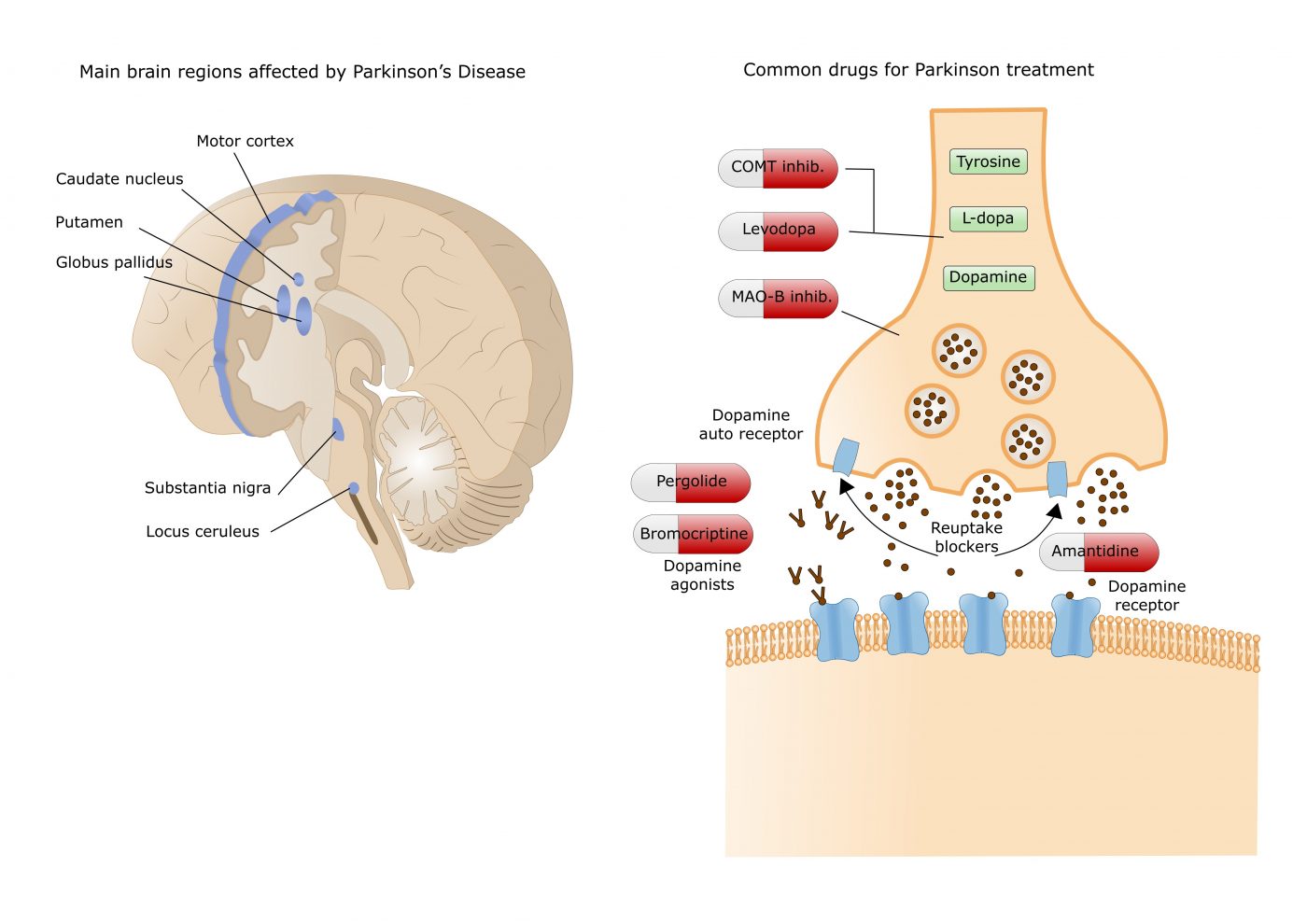

Our knowledge about Parkinson's disease is limited. The official narrative is that Parkinson's disease is characterized by progressively expanding nerve cell death originating in substantia nigra, a midbrain region that supplies dopamine to the basal ganglia, a system involved in voluntary motor control. The cause of this cell death is poorly understood but involves alpha-synuclein aggregation into Lewy bodies within the neurons. Substantia nigra is really a tiny part of the brain, and other studies have already revealed a wider involvement in the brain. I guess we would make significant progresses in the disease knowledge if we acknowledge that if alpha-synuclein is involved in Parkinson's disease, it is unlikely its effects are limited to a tiny portion of the brain, as alpha-synuclein is abundant in the brain, while smaller amounts are found in the heart, muscle and other tissues and Lewy bodies are in the midbrain and the cortex.

Another interesting article is: "Ophthalmate is a new regulator of motor functions via CaSR: implications for movement disorders".

While the official narrative is that Parkinson's disease is characterized by neuronal death in substantia nigra, which supplies dopamine to the basal ganglia, a system involved in voluntary motor control, it has been known for decades that robust motor activity can happen in Parkinson's mouse models when L-DOPA conversion to dopamine is blocked! The motor improvement is larger than in the conventional case where L-DOPA is metabolized in dopamine. The authors hypothesized that there was an alternative pathway or mechanism, independent of dopamine signaling.

The authors sought to determine the metabolites associated with the pronounced hyperactivity observed. They observed that the peak in motor activity induced by inhibiting L-DOPA conversion into dopamine in Parkinson’s disease mice was associated with a surge (20-fold) in brain levels of the tripeptide ophthalmic acid (also known as ophthalmate in its anionic form). When they administered ophthalmate directly into mice's brains, it rescued motor deficit in a dose-dependent manner.

The team investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying ophthalmate’s action and discovered, that ophthalmate binds to and activates the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR). To strengthen their findings, they verified that a CaSR antagonist inhibits the motor-enhancing effects of ophthalmate.

A link between Parkinson's disease and the calcium-Sensing Receptor is interesting as CaSR also Mediates β-Amyloid production. There is only one other publication that explicitly links the disease to CaSR. Calcium acts in a number of signal transduction pathways as second messengers, so maybe it is not wise to read too much about a link between Parkinson's disease and CaSR, but finding that lack of dopamine is not the main cause of Parkinson's disease, is a major finding.

Indeed, Parkinson’s disease is characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and the presence of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites, which mainly consist of aggregates of α-synuclein. It is believed that α-synuclein aggregates poison the brain's cells and indeed especially this tiny part of the brain named "substantia nigra". Yet like other protein aggregates, they may form to protect the brain against some external aggression or stressing event. So the biological mechanisms underlying α-synuclein relationships with dopaminergic neurons have never been firmly established.

Indeed, Parkinson’s disease is characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and the presence of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites, which mainly consist of aggregates of α-synuclein. It is believed that α-synuclein aggregates poison the brain's cells and indeed especially this tiny part of the brain named "substantia nigra". Yet like other protein aggregates, they may form to protect the brain against some external aggression or stressing event. So the biological mechanisms underlying α-synuclein relationships with dopaminergic neurons have never been firmly established.

The hexosamine pathway produces N-linked glycans, essential molecules that support protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum.

The hexosamine pathway produces N-linked glycans, essential molecules that support protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. This initiative may be driven by the pharmaceutical industry's frustration over unsuccessful clinical trials. By using molecular criteria, clinical trials could achieve higher success rates, despite the persistence of clinical symptoms. This strategy is already evident in the Alzheimer's field, where several drugs have been approved without significantly alleviating symptoms.

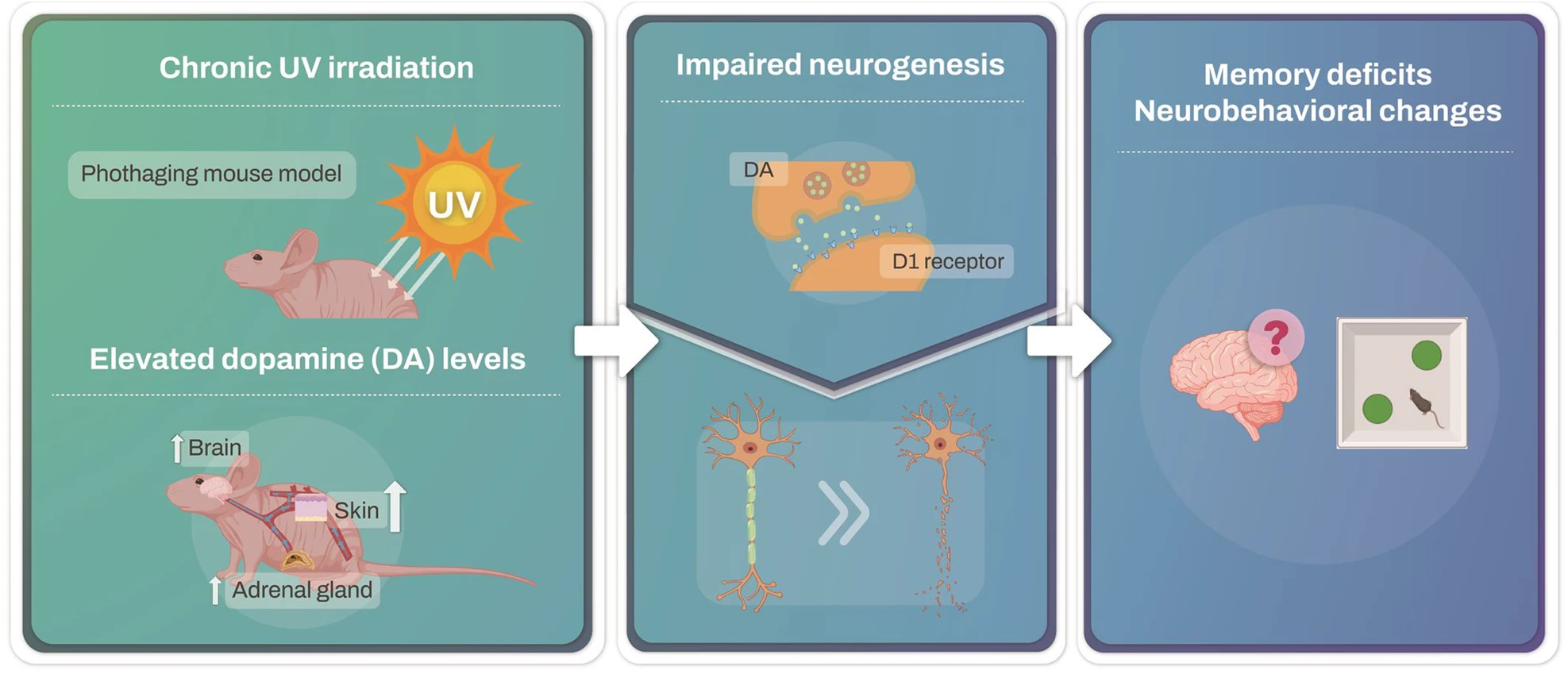

This initiative may be driven by the pharmaceutical industry's frustration over unsuccessful clinical trials. By using molecular criteria, clinical trials could achieve higher success rates, despite the persistence of clinical symptoms. This strategy is already evident in the Alzheimer's field, where several drugs have been approved without significantly alleviating symptoms. These naked mice allow easy experiments on the skin, application of topical agents, and exposure to UV. To investigate the effects of UV irradiation on hippocampal memory and neurogenesis, mouse skin was irradiated with UV for 6 weeks. After 6 weeks of UV irradiation, the mice underwent behavioral tests. Photoaged mice exhibit impaired cognitive function and neurogenesis.

These naked mice allow easy experiments on the skin, application of topical agents, and exposure to UV. To investigate the effects of UV irradiation on hippocampal memory and neurogenesis, mouse skin was irradiated with UV for 6 weeks. After 6 weeks of UV irradiation, the mice underwent behavioral tests. Photoaged mice exhibit impaired cognitive function and neurogenesis. In response to UV exposure, no significant changes in dopamine levels were detected in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), substantia nigra (SN), or hippocampus (HPC). However, dopamine levels in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and hypothalamus (HT) significantly increased.

In response to UV exposure, no significant changes in dopamine levels were detected in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), substantia nigra (SN), or hippocampus (HPC). However, dopamine levels in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and hypothalamus (HT) significantly increased. Bien qu'il y est eu de nombreuses études sur la sujet, des

Bien qu'il y est eu de nombreuses études sur la sujet, des  Currently available dopamine treatments work either by increasing dopamine levels (e.g. levodopa, COMT and MAO-B inhibitors) or by directly activating dopamine receptors in the striatum, an area deep in the brain.

Currently available dopamine treatments work either by increasing dopamine levels (e.g. levodopa, COMT and MAO-B inhibitors) or by directly activating dopamine receptors in the striatum, an area deep in the brain.